On inclusive presentations

I’ve recently attended several conferences and talks both in person and remote. I’ve had the pleasure to see amazing professionals sharing their knowledge and experiences. However, there’s several repeating patterns that I keep seeing and that I wish to see fading away soon.

Preparing a presentation takes an insane amount of time, I know that! And I’m sure the ultimate goal for the people delivering one is that the message lands, is understood, and hopefully it can be repeated in other events, or uploaded to the internet to reach even a broader audience. But wait, things get interesting here.

According to WHO, about 15% of the world’s population lives with some form of permanent disability.

Stereotypical views of disability emphasize wheelchair users and a few other “classic” groups such as blind people and deaf people.

However, there’s many other disabilities that are not as visible as the stereotypical ones. And if we think of a disability as a mismatched human interaction instead of a health condition, there’s even a greater amount of people facing a disability: temporarily (they broke an arm) or situational (they are in a very loud place where they cannot hear what you say). If you think of a conference in a big venue, you might not notice anyone in the audience with one of those stereotypical disabilities, but there will be at least four, five or six rows of people sitting at the very back of the audience who need to read your slides from a very large distance, in the dark, and facing a situational vision impairment. To add to that, if your conference is uploaded to a video platform, you don’t even know who will be watching and in which conditions. So, you get my point.

How can you land an inclusive and accessible presentation?

Here’s some tips I learned during these past years on how to make your presentations more inclusive and accessible for everyone. Because if you solve for some, you can extend to many:

1. Trigger warnings

Even before you start with your talk, consider if there’s any topic that might be sensitive to the audience. Will you be talking about abuse, violence, emotional disorders, or a topic that could trigger someone in the audience (present or future)? If so, this is the right moment to explain to the audience what are the main potential triggers you’ll be touching on and allow time for people to leave or stop watching while you introduce yourself, without causing an uncomfortable moment if leaving in the middle of your talk. Consider also adding the trigger warning visibly written in your intro slide, and ask the organization to add it in the description of the video if there will be one.

2. Introduce yourself

Some people might have a sight disability, as we mentioned, it could be that they are blind people or they’re at the very back of the audience, or maybe they’re listening to your talk with an airpod while preparing the kid’s breakfast. Explain in very simple words what are the traits you’d like to be recognized for, or that you think are important. What are you wearing, your ethnicity (if relevant), what color is your hair? Giving a small visual description or indicators of how you look, will help people situate you during the rest of your talk.

3. Explain the design of your slides if relevant

If the design of your slides has some kind of wink to a certain topic or theme, will drive certain emotions to the audience, or will place them in a specific state of mind, it is important to explain it in advance. (ie: ‘the slides in this presentation will all be themed with a pirate aesthetic, using old maps and pirate symbols’). Of course, if you’re using a regular template or the design of your slides has no relevance in your story, probably there’s no need for explaining this.

4. Show an index or a summary of your talk

If it’s a complex topic or a long story, it helps showing an index of your talk at the very beginning so the audience know what the narrative will be and make them feel in control, and if you’re going for a more story telling format having a recap at the very end can be very useful to retain the key ideas. This technique, like the other ones, not only helps people with adhd, but also helps with a tired audience after a long day of talks, people willing to take notes, or to index the contents of your talk later on. I personally find this very useful when preparing a talk. That’s my go-to method to make sure not to digress and have a clear narrative.

Bonus track: If you feel comfortable with the idea, share the slides with the audience before starting, using a URL shortener that you can say out loud. You can also share a URL with a transcript of what you’ll say, and/or links and resources that will be mentioned during the talk.

5. Use text to support your slides, (but not that much text)

Supporting your slides with text helps people to follow your speech easily. When a deck is just a bunch of pictures one after the other, it can cause some disconnect with the audience who can easily lose track of what the headline of that section was, or might be trying to connect the image with words that you hadn’t spilled yet, causing them to disconnect from your idea. To the opposite, if there’s a bunch of text in your slide, people will be reading that instead of listening to you. So; find a middle ground. Oftentimes headlines or 2-3 bullet points are more than enough.

Text size and weight are also very important. This one seems very obvious, but believe me, it’s not. Use fonts that are big enough to be seen from the back of the audience, and if you think the text doesn’t fit well, probably there’s too much text in that slide. Refrain to make it smaller just so you can type more. Thin typefaces can also be problematic, specially if the talk will be streamed and compressed, it can make your text completely illegible.

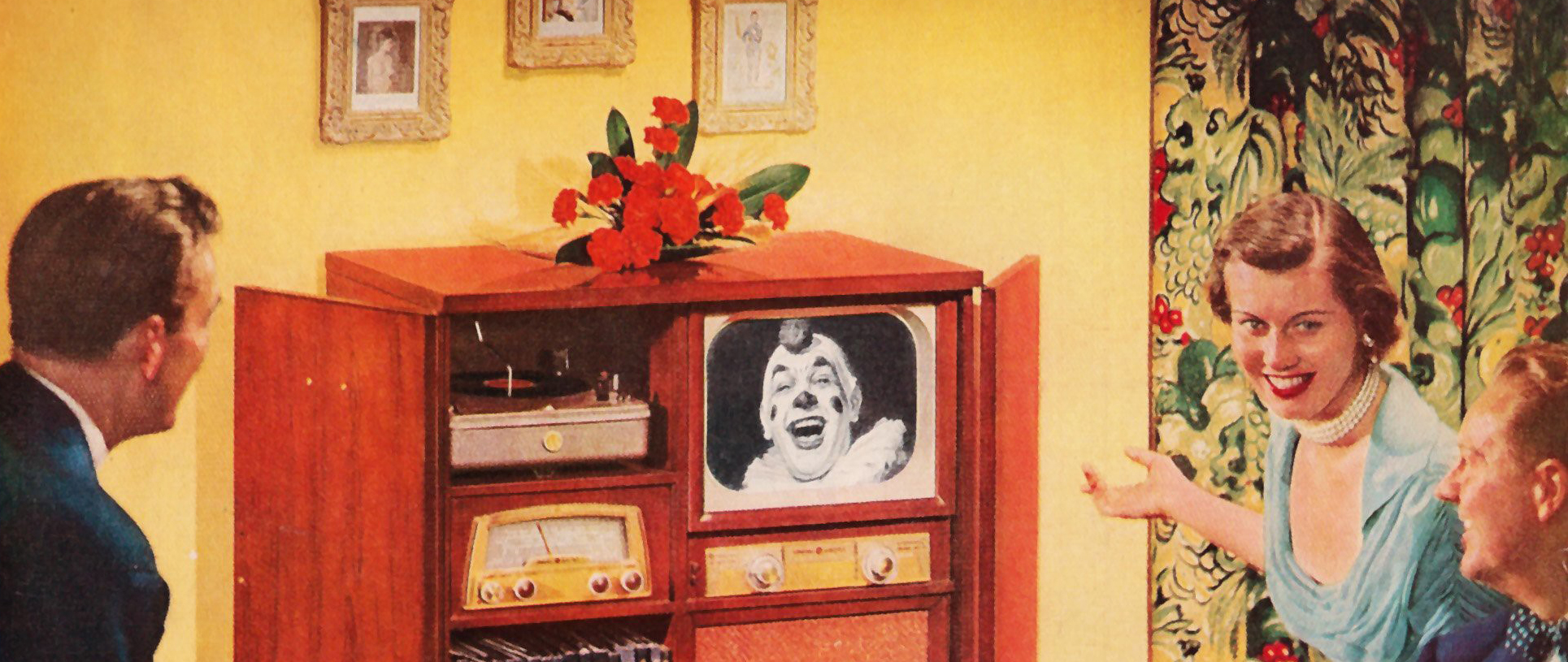

6. Use ALT IRL

Most of us are familiar with ALT text in images, in social media, websites or apps. ALT text is basically alternative text to an image, which serves the purpose to explain it in case the user cannot see it or, oh, surprise, it doesn’t load in your browser because reasons (the image is gone, internet is slow, etc.). If you are using images that aren’t merely decorative or aren’t represented in your speech, explain them. How many times have you listened to one of those podcasts with video and they show something to the live audience and all laugh at the joke but you are running on the street or folding clothes? Yes. You got it. You know how it feels. Don’t rely on an image punchline without verbally expressing it, or you might be losing half of your audience. Consider also adding the ALT text written below the image for those who might not be able to comprehend it or simply don’t know the reference. The same goes for charts or graphics. Explain what we should read from them, don’t have them just hanging behind you hoping for the audience to decipher them while you talk.

7. Don’t use animations

I know this sounds savage. But hang in here. Fast animations and high speed animated gifs in loop, might seem fun, but can be also highly disturbing, and may have a bad impact on those with motion or vestibular disorders. We are all familiar with all the studies done for television in the 90s, where certain cartoons and animations were causing seizures and other kinds of issues to some people. Fast animations can make your audience wildly dizzy, especially in a live conference with low light in the audience and high bright in the projected image. If you want to use animated gifs, make sure they aren’t fast paced, they don’t flash more than three times in any one second period, and that they don’t loop more than once. I still remember a recent talk where you could see how everyone had to lower their head to avoid the effect. So, yes, you can use animations, but you need to be very careful, and if you cannot handle the requirements, then I refer back to the headline of this point.

8. Add subtitles to your videos

This one is easy: if you want to display a video, make sure it has subtitles in it.

If your video doesn’t have a proper audio track that makes it understandable, then you should explain what are we seeing using your own words (…music doesn’t count as an understandable audio track).

9. Control the contrast

Don’t use dark fonts on dark backgrounds, or light fonts on light backgrounds. Make sure the text and background have enough contrast for it to be differentiated. When in doubt you can use an online color contrast checker. Or simply use a template that already has accessibility checks done to it.

On the same vein, refrain from using charts and graphics that rely solely on color to be understood. For example, column bars with similar colors, or line charts with thin lines of colors with not enough contrast. Something that can be helpful is using shapes instead of color, or adding labels on top of them.

10. Beware of cultural contexts

When in international conferences, or those that will be broadly available afterwards, it might be a good idea to make sure to explain your references when talking about local politicians, laws, news, or public personalities. Not everyone in the audience will know them like you do. Briefly adding 4 or 5 extra words after the name or the fact to clarify should be enough. It is important to take into account things like writing dates with their month name, instead of using numerical data formats which vary geographically, taking into account that Winter might equal sun or snow at the same time depending on where you are, or that not everyone knows your country’s traditions.

Being mindful of the language you use is also a key part of this.

Inclusive language is a language style that avoids expressions that its proponents perceive as expressing or implying ideas that are sexist, racist, or otherwise biased, prejudiced, or insulting to particular group(s) of people; and instead uses language intended to avoid offense and fulfill the ideals of egalitarianism, social inclusion and equity.

One of my favorites (not) is when in conferences folks use ’your grandmother’ or ’your mother’ as synonym of illiterate. Nope, nope.

I hate it that I ended up with 10 points to land an inclusive presentation as any other LinkedIn post from internet gurus which always have 5 or 10 points, but one of the premises of this blog is that I’d just post here without much worry. One thing I can promise: no chatGPT was used for this article.